Dec 10, 2018

Getting settled in with family health care in Japan

I took my son to his city-directed group health check last week. For those who haven’t yet had the joy of going through this, in Japan, instead of doing personal appointments for infant/toddler wellness checks, the city organizes group sessions with a bunch of kids based on birth month. You walk into a big room, get handed a number and a bunch of forms, get lectured for a bit, and then go through a station-to-station health and aptitude test.

With two young children at home and being the principal Japanese speaker, I am now a veteran of these painful exercises. But this time proved a little different.

As I was filling out the forms, I really thought about two things. First, I realized just how different expectations are in Japan and back home in the United States. Second, I thought about how challenging living as an expat can be on the mental health of parents.

First, I’ll start with few key differences I noticed at the health check.

1) The forms are not gender neutral. There is an inherent expectation that the individual bringing the child to these health checks is the mother, so all the questions are asked from a mother’s perspective.

2) There is implicit concern over paternal involvement. Some of the questions directly asked how much support the father gives to child rearing—made more ironic since I was the one filling out the form.

3) There is an assumption that the grandparents are intimately involved. I don’t know if it’s different in the cities, but out here in the country, the forms presume that at least one grandparent offers regular care to the child.

I have Japanese relatives, and I’ve been in Japan long enough to know that the “traditional” situation is for the father to work all the time, the family to live with one or more grandparent who helps with the children, and for the mother to be a stay-at-home mom, but that’s certainly not the norm in the United States and it hasn’t been the norm for many Japanese families in a while.

It made me wonder when the Japanese medical bureaucracy would catch up to present day circumstances, but how long does it take any bureaucracy to catch up?

The point is that it takes some getting used to. Just be prepared at health checks for these inherent assumptions, and be ready to explain your own unique circumstances if they do not apply.

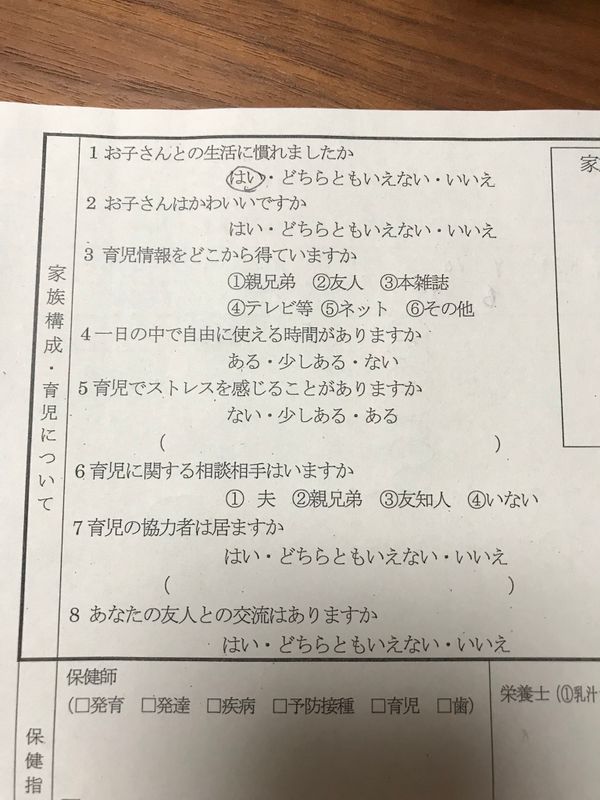

The mental health issue came to mind when I got to this form (I actually had to stop after answering the first question so I could take a picture):

Allow me to walk you through the questions:

1) Did you hope for a life with children? yes, no, can’t say either way

2) Do you think your child is cute? Yes, no, can’t say either way

3) Where do you get information on child rearing? Parents/Siblings; friends; books; television, etc.; Internet; Other

4) In a day, do you get time to yourself? yes; a little bit; none

5) Do you ever feel stressed raising a child? No; sometimes; yes

6) Do you have someone to discuss child rearing with? Spouse; Parents/Sibling; Friends/Acquaintances; no

7) Is there someone who helps you raise the child?

8) Do you interact with friends?

I understand the purpose of the form. I really do. Parenting is hard. For some people, it is not what they expected it to be, and for others still, it may not be what they wanted at all. Mental health for parents is something that cannot and should not be ignored.

But here’s my issue: this was a form they handed out for us to fill out while minding our children in a room with thirty other people plus medical staff. Who would be honest on that form? A form that is asking for some serious introspection and exposure in a setting that is not at all conducive to it.

So what should you do if you’re an expat and need help? If you’re capable of putting yourself out there via a form, then by all means, use the city-directed health check as an opportunity to seek assistance. If that is too difficult, it is possible to submit the form discreetly to the city office’s health section. They can assist you in finding professional assistance, whether it is childcare or mental health assistance.

I have found that my local pre-school/daycare is very supportive for families, as well. They have a government subsidized daily payment option if day-to-day child care is needed (it’s 1,200 yen for the whole day, with meals/snacks included), and the staff are very willing to offer recommendations on how best to support your child’s needs if you ask.

The last recommendation is to recognize that if you are struggling, you aren’t the only one. Being a parent is hard enough. Being a parent in a foreign country with limited support base and having to learn an entirely new system on top of figuring out child rearing is incredibly challenging. Use City-cost. Use other outlets. Engage with other parents, ask questions, vent. Take those steps to make sure that you know that you aren’t alone, because you aren’t. All of us who post on this site do so because we’re in the same boat. We’re trying to help others and get help ourselves.

So, in sum, I would say, try to manage expectations working through Japanese processes. It can be frustrating, but hopefully this post and others like it will help prepare you for it. Second, remember that your mental health as a parent is as important as your child’s health—they go hand-in-hand, really. These city-directed health checkups aren’t really the best way for addressing these issues, but it’s one option. And remember that while all of us expats on this site aren’t face-to-face, we’re all in this whole thing together! Gambatte!

Hitting the books once again as a Ph.D. student in Niigata Prefecture. Although I've lived in Japan many years, life as a student in this country is a first.

Blessed Dad. Lucky Husband. Happy Gaijin (most of the time).

0 Comments