Jul 13, 2021

Aizu’s lacquer artisans fighting to keep culture from becoming mere heritage

While the preservation of heritage is generally something celebrated, some people are not yet ready to consign current, traditional livelihoods to the past however precarious the current circumstances surrounding them might be.

In the city of Aizuwakamatsu in western Fukushima Prefecture, lacquer specialist Suzuzen has been a mainstay of the region's celebrated Aizu-nuri lacquer industry for nearly 190 years.

The craftspersons at Suzuzen are now, though, having to rethink their position in the industry if they are to make it beyond two centuries of doing business -- if indeed there is even an industry left to speak of.

"The way I think about it is that until 50 years ago lacquerware was an “industry.” Now, from the point of view of our work, we have to think about it as a “culture,”" said Kousai Nakamura, a lacquer craftsman at Suzuzen, during an interview in Aizuwakamatsu in February.

Aizu's lacquer industry rode its production peak up to around half a century ago and has since been in a decline that has seen production shrink to around a tenth of what it was during its pomp. Lifestyle changes and a demand for cheaper goods are the main factors behind the decline, according to Nakamura.

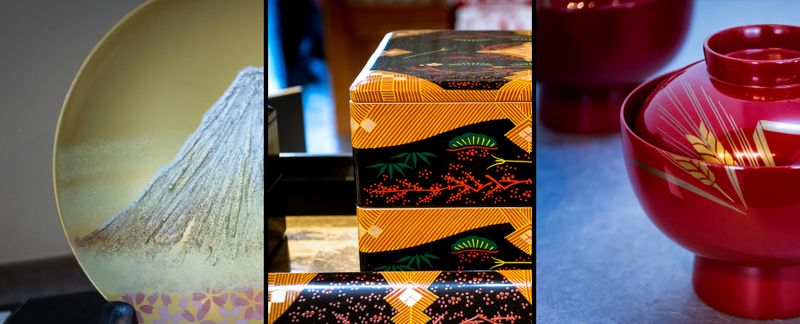

The history of Aizu lacquer dates back to the late 16th century when its production was encouraged by the feudal lord Gamo Ujisato who called upon the skills of craftspersons and artisans of his previously held territory (in present-day Shiga Prefecture) to introduce lacquer to the Aizu region.

Today, showcasing the historical and cultural legacy of the Aizu clan samurai has been seen as a key approach on the part of the local government and other organizations in promoting tourism to the Aizu region.

At least some of the local samurai’s cultural legacy can be found in Aizu lacquer. First lord of the Azu domain Hoshina Masayuki (1611-1673), who is credited with cementing Aizu clan samurai loyalty to the ruling shogunate, is said to have done much to help the local lacquer industry, including in the preservation of lacquer trees.

It was with the seal of approval from the Edo Bakufu -- the Edo period government supported by the samurai -- and the recognition of the lord of the Aizu domain, that Suzuzen, then named Suzuki-ya Lacquerware Store, established itself as a lacquerware wholesaler in 1832.

The wholesalers took their Aizu lacquerware to Edo (present-day Tokyo) and Shinshu (present-day Nagano) among other parts of Japan, showcasing it as something that had not only artistic value but also as something that had application in daily life. This led to a rapid increase in its popularity.

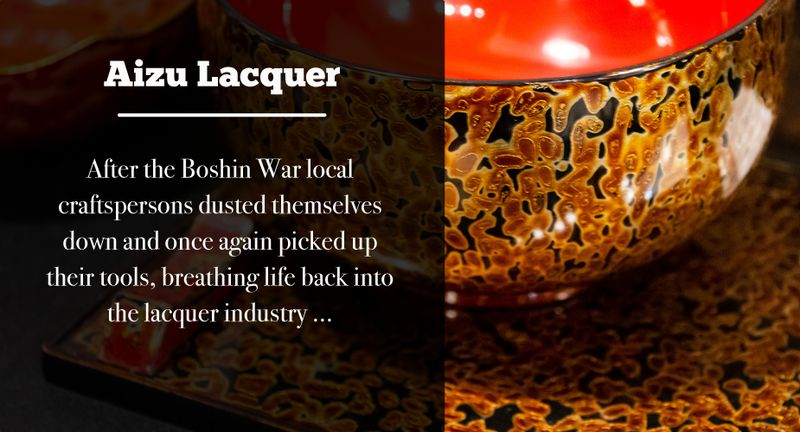

Despite the Boshin War (1868 - 1869) hitting Aizu’s lacquer industry hard, as well as removing from power the samurai who had done much to support it, after the war local craftspersons dusted themselves down and once again picked up their tools, breathing life back into the industry.

In 1897 Suzuzen began to produce lacquer furniture starting with the “ikou,” an item on which to hang kimono. Through mechanization, mass production of ikou became possible, something which served as a key moment in the development of the lacquerware industry with Suzuzen eventually accounting for 70 percent of ikou production nationwide.

With competition increasing during Japan’s post-war years the 4th generation of owners at Suzuzen began to work with the plastic Bakelite as production methods became evermore mechanized.

“Changing from wood to plastic brought about a change to mass production,” said Nakamura.

“With mass-produced factory plastic we were able to apply the lacquer by spraying so we switched to this cheaper plastic. It's not just Suzuzen. Other producers did the same.”

Production efficiency, while it may have served to boost output, has seen the industry lose craftspersons armed with the original, traditional skills of Aizu-nuri. Something being felt by the industry, such as it may be, today.

(According to a February 2020 press release from the DENSAN Association (Traditional Craft Industry Promotion Association) there were approximately 3,900 traditional craftspersons currently active in Japan, as recognized by the association.)

“I think that traditional industries and crafts are in a very tough situation. I think that demand will continue to decline,” said Nakamura.

So, where once Suzuzen showcased Aizu’s lacquerware as something which had value beyond merely the artistic, the producers are now eyeing their survival in pre-mass production traditions.

Some of the fruits of these traditions, remarkably elaborate in many cases, can be viewed at Suzuzen’s Bijutsu-zo art warehouse in downtown Aizuwakamatsu. The Bijutsu-zo exhibits examples of Aizu lacquerware from iconic Aizu artists and craftspersons, some pieces revealing designs and styles that can only be found in lacquerware (former) wholesalers like Suzuzen.

Lacquerware featuring the curiously named “kin mushi kui” pattern can also be seen (and purchased) at the Suzuzen facility -- kin mushi kui being the name of the signature Aizu lacquer pattern named for its resemblance to an insect bite in gold.

(Lacquerware featuring Aizu's signature kin mushi kui pattern)

Along with Suzuzen’s Aizu-nuri Folklore Hall -- which explains the history of Aizu-nuri and the Suzuzen facility -- the Bijutsu-zo is an example of the people at Suzuzen preserving their, and the local industry’s, heritage, even if they’re not ready to direct all of their energy toward this.

“Originally Aizu produced tableware, then going on to include furniture and other household items. This remains the main focus of production today but we're also looking to take a new approach,” said Nakamura.

“As for the material, we're not just using wood, we apply lacquer to fabrics, metals, and glass to create items that now include accessories. We’re doing things like this to help us survive.”

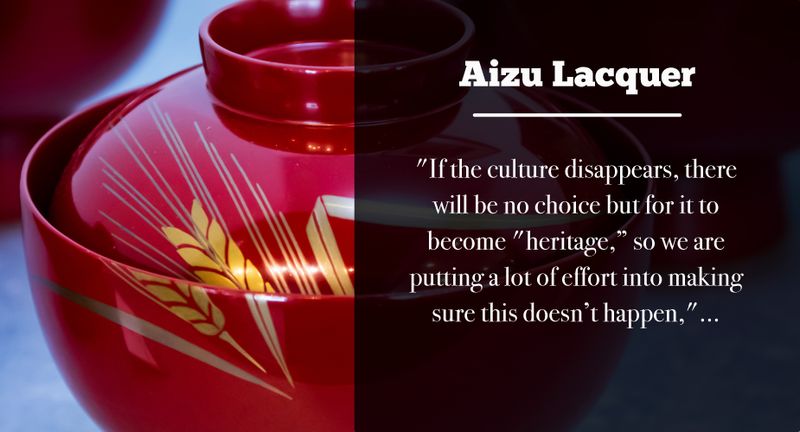

"If the culture disappears, there will be no choice but for it to become "heritage,” so we are putting a lot of effort into making sure this doesn’t happen," he said.

As of January 2021, Aizu-nuri is one of 236 entries on a list of traditional crafts as recognized by the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry. These traditional crafts are seen by the ministry as those that produce items made by hand using traditional materials and processes with more than 100 years of history.

Despite the recognition (or perhaps reflective of it) many of these “traditional crafts” are facing struggles similar to those faced by Aizu lacquer, according to Nakamura.

“It seems strange to say everything under the umbrella of “traditional crafts,” but things like ceramics, washi (paper), textiles, e-rousoku (painted candles) and others, most of these industries are in the same situation. Uchiwa (traditional fans), too,” he said.

Nakamura does feel though that Aizu and Aizu lacquer has at least one factor going its way in the fight for survival.

“I still think Aizu lacquer is somewhat fortunate, for the same reason that Kyoto is the most fortunate place,” he began to explain.

“Aizu is a tourist destination and in tourist destinations you get a variety of people gathering and we can make products for these people, be it lacquerware, anything, so in places where tourism and production are connected, traditional crafts can somehow get by. Kyoto, Kanazawa, Aizu, places like this, they all still have traditional craft industries,” he said.

In the store at Suzuzen visitors can see and purchase a large variety of Aizu lacquerware as well as see examples of how craftspersons are adapting to develop products for modern living. Store staff explained that most customers here are tourists shopping for souvenirs or local people looking for gifts to present at “oiwai,” or traditional Japanese celebrations.

The outbreak of the novel coronavirus and subsequent pandemic has meant sometimes having to close the store, according to staff, the virus crises presenting another challenge to Suzuzen’s efforts at keeping the Aizu lacquer culture, if not its industry, in the present rather than be consigned to the past.

The outbreak of the virus has seen visitor numbers in the city Aizuwakamatsu drop by as much as 80 percent compared to visitor numbers in 2019, according to Aizuwakamatsu City officials.

Speaking in February, Ryoji Nihei of the city’s tourism and commerce department explained the impact on the wide-reaching local industry.

"We have many historical attractions here, but as well as the tourist attractions and accommodation facilities, there are the restaurants, the traders that support these businesses," said Nihei.

"Tourist numbers decreased dramatically and it has had a huge effect on the city."

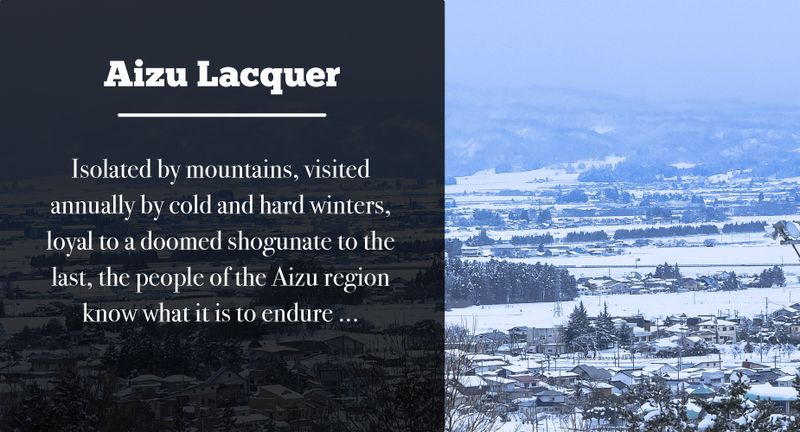

Isolated by mountains, visited annually by cold and hard winters, loyal to a doomed shogunate to the last, the people of the Aizu region know what it is to endure. Indeed, local crafts like Aizu lacquer -- durable, sustainable -- are the very products of this endurance. If anyone is equipped then, in spirit at least, to hold out until the tourists return, to prevent “culture” becoming “heritage,” it’s the people of the Aizu region.

Related:

Future of Ouchijuku’s kayabuki roofs rests in hands of skilled few

Family of brewers pursues clean energy future for Fukushima region

0 Comments